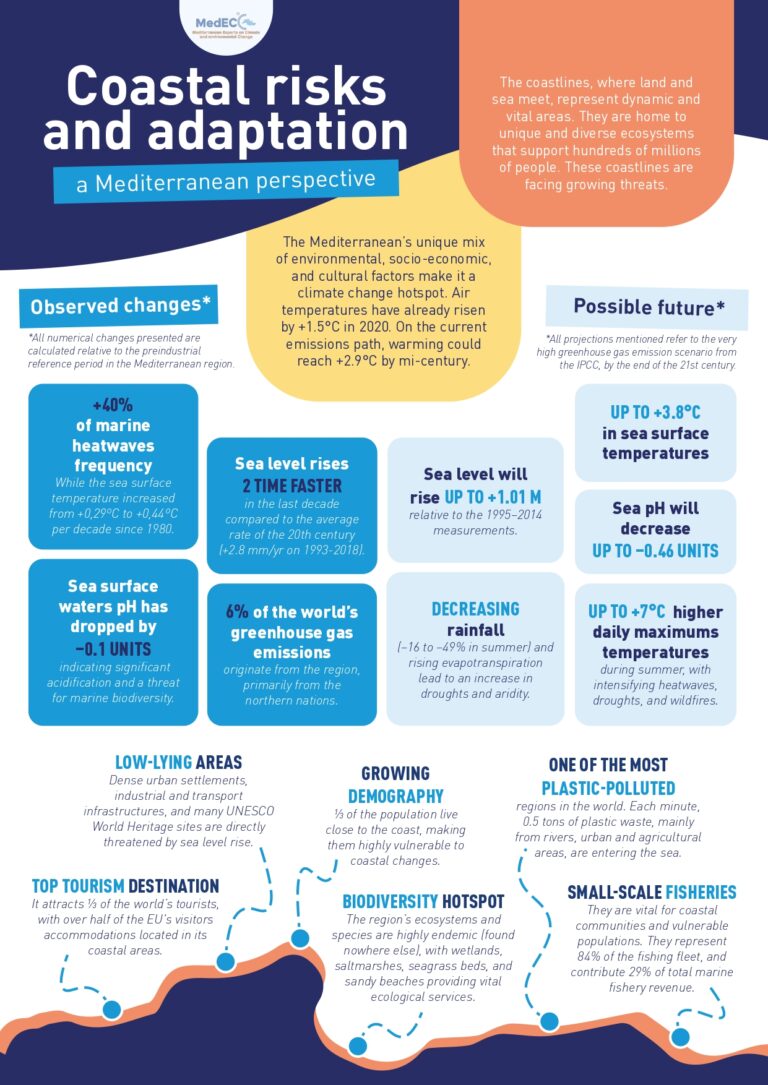

Climate change threatens marine and coastal ecosystems in the Mediterranean region. Warming, sea level rise, and ocean acidification are occuring there more intensely and rapidly than the global average. A recent study led by GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel reviewed 131 scientific papers in a meta-analysis to understand how Mediterranean ecosystems are already being affected – even under moderate future warming.

Journal Reference: Hassoun, A.E.R., Mojtahid, M., Merheb, M. et al., ‘Climate change risks on key open marine and coastal mediterranean ecosystems’, Scientific Reports 15, 24907 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07858-x

Article Source: Press Release/Material by Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel (GEOMAR)

Warming sea and rising risks

Temperatures in the Mediterranean are currently rising to record levels. With an average water temperature of 26.9°C, July 2025 was the warmest since records began for the Mediterranean Sea, according to the Copernicus Earth Observation Service. In some regions, temperatures rose above 28°C. This warming combined with other stressors such as overfishing, pollution, and habitat destruction is a major factor threatening marine and coastal habitats.

“The consequences of warming are not only projections for the future, but very real damages we are witnessing now. The continuing rise in temperatures, sea level and ocean acidification cause severe risks for the environment in and around the Mediterranean Sea,” says Dr. Abed El Rahman Hassoun, Biogeochemical Oceanographer at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel.

Meta-study on climate change scenarios

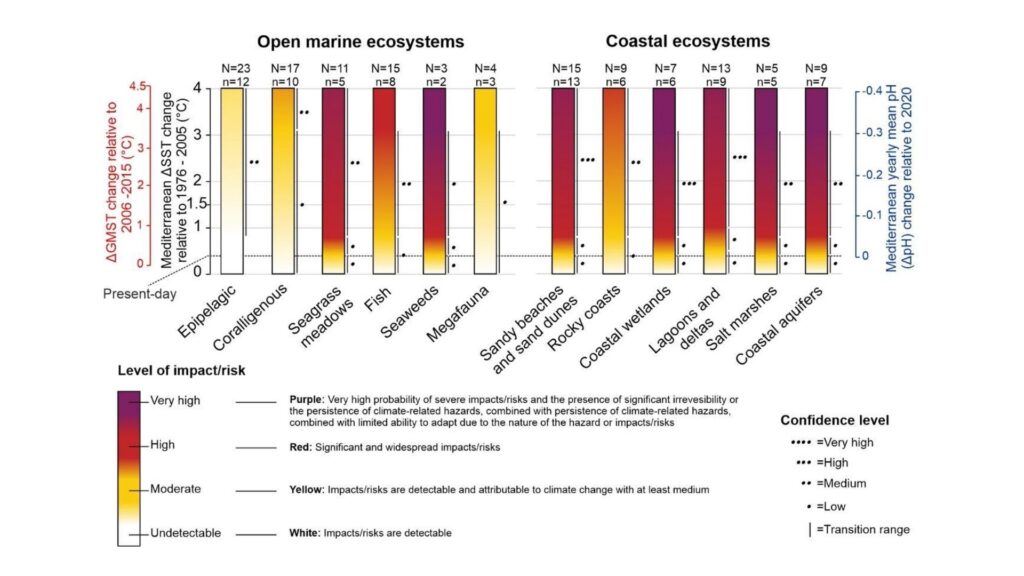

Together with Prof. Dr. Meryem Mojtahid, Professor of Paleo-Oceanography at the University of Angers and at Laboratory of Planetology and geosciences (France), researchers evaluated the effects of climate change on marine and coastal ecosystems in the Mediterranean region. For the first time, they produced a so-called ‘burning ember’ diagram for Mediterranean marine and coastal ecosystems – a risk assessment tool showing how rising temperatures increase the likelihood of severe impacts, originally developed by the IPCC. The study also draws on the MedECC work and its first Mediterranean Assessment Report under the name MAR1.

“The diagram clearly shows how strongly climate change threatens key ecosystems. I hope our results will help raise awareness and inspire real action to protect these unique ecosystems,” says Meryem Mojtahid.

Mediterranean as a “Climate Change Hotspot”

The Mediterranean Sea is semi-enclosed, connected to the global ocean only through the Strait of Gibraltar. As a result, the Mediterranean Sea is warming faster and acidifying more strongly than the open ocean. Between 1982 and 2019, surface seawater temperature already increased by 1.3°C, compared to a global average increase of 0.6°C. The Mediterranean Sea is referred to as a ‘hotspot of climate change’, and scientists consider it as a natural laboratory reacting faster and more strongly to climate pressures than the open ocean, while at the same time concentrating multiple drivers and stressors in a relatively small, well-observed system.

“What happens in the Mediterranean often foreshadows changes to be expected elsewhere, so the Mediterranean Sea acts like an early warning system for processes that will later affect the global ocean,” says Abed El Rahman Hassoun.

Future scenarios: every tenth of degree counts

If international climate protection targets are met in the coming years, some environmental changes could still be slowed. Two IPCC scenarios – known as RCPs, or Representative Concentration Pathways – can be used to illustrate this:

- In a medium emissions scenario (RCP 4.5), emissions will stabilise over the next few years thanks to moderate climate policies. Even in this case, the Mediterranean Sea is expected to warm by an additional 0.6 to 1.3 °C (compared to current values) in 2050 and 2100 respectively.

- In contrast, the high emissions scenario (RCP 8.5) describes the “business as usual” path with continuously rising emissions. In this scenario, additional warming would likely range between 2.7°C and 3.8°C by 2050 and 2100 respectively. Such warming, together with sea level rise and ocean acidification, would have significant disruptions on ecosystems: seagrass meadows would be lost, coral reefs might witness significant damages, and severe chain reactions would occur in food webs.

“These scenarios show: We can still make a difference! Every tenth of a degree counts!” says study leader Abed El Rahman Hassoun. “Political decisions made now will determine whether ecosystems in the Mediterranean Sea collapse, partially or totally, or remain functional feeding the ecosystem services they provide. At the same time, our study also shows that even with moderate climate protection and an additional 0.8°C warming, we must expect some consequences. Thus, our focus should be on minimizing the impacts as low as possible.”

Impacts on Marine Ecosystems

The researchers examined a wide range of marine ecosystems: from seagrass meadows to fish and macroalgae, as well as marine mammals and turtles. Warming and acidification of the Mediterranean are altering entire communities:

- Plankton species are shifting, and toxic algal blooms and bacteria are occurring more frequently.

- With an additional warming of 0.8°C, seagrass plants such as Posidonia oceanica would decline massively and disappear completely by 2100.

- Seaweed species such as Cystoseira would also decline, while populations of heat-loving invasive algae could increase.

- Fish stocks are under pressure from +0.8 °C as well: they could shrink by 30 to 40 percent, shift northwards, and make room for invasive species such as the lionfish, which threatens biodiversity.

- Corals, probably due to their long evolutionary history, are relatively more resilient than other ecosystems, as they are at moderate to high risk from +3.1 °C.

- Data on marine mammals and sea turtles are limited, but changes in feeding grounds, migration behavior, and energy budgets are likely to occur.

Coastal ecosystems: highly vulnerable

Due to the combined effect of warming and sea-level rise, coastal ecosystems in the Mediterranean Sea are especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The zone affected includes areas up to ten meters above sea level, such as dunes and rocky coasts.

Rising sea levels increase coastal erosion and thereby threaten the nesting sites of sea turtles – more than 60 percent could be lost.

Even at an additional warming of just +0.8 °C, the risk rises significantly: sandy beaches and dunes are particularly endangered, and rocky coasts also lose habitat and biodiversity, although they are somewhat more resilient.

Wetlands, lagoons, deltas, salt marshes, and coastal aquifers are also affected and can experience considerable damage already at +0.8°C to +1.0°C. Here, the loss of important plant species, the spread of invasive species, and large-scale vegetation changes are very likely.

At the same time, rising sea levels can lead to reduced precipitation and consequently water scarcity. From +1.0 °C onward, the risks are expected to increase further due to flooding and higher nutrient inputs.

“We found that Mediterranean ecosystems are remarkably diverse in how they respond to climate-related stress. Some are more resistant than others, but none are invincible”, says Meryem Mojtahid. “Only strict climate protection measures can keep the risks at a level to which ecosystems can still adapt. Through this study, we were able to make visible that even a comparatively small increase in temperature and other climate change-related stressors has significant effects. Now it’s time to turn knowledge into action”, adds Abed El Rahman Hassoun.

Research gaps and the need for action

For several ecosystems, scientific studies for the assessment of risks are still limited. There are only few projections for deep-sea habitats, salt marshes, macroalgae, and megafauna.

Significant geographical gaps also remain, particularly in the southern and eastern Mediterranean, leading to a possible underestimation of risks in underrepresented countries.

Moreover, long-term observations that address multiple stressors such as pollution and invasive species simultaneously are lacking.

Addressing these gaps will require stronger interdisciplinary research efforts and expanded monitoring, especially in underrepresented regions